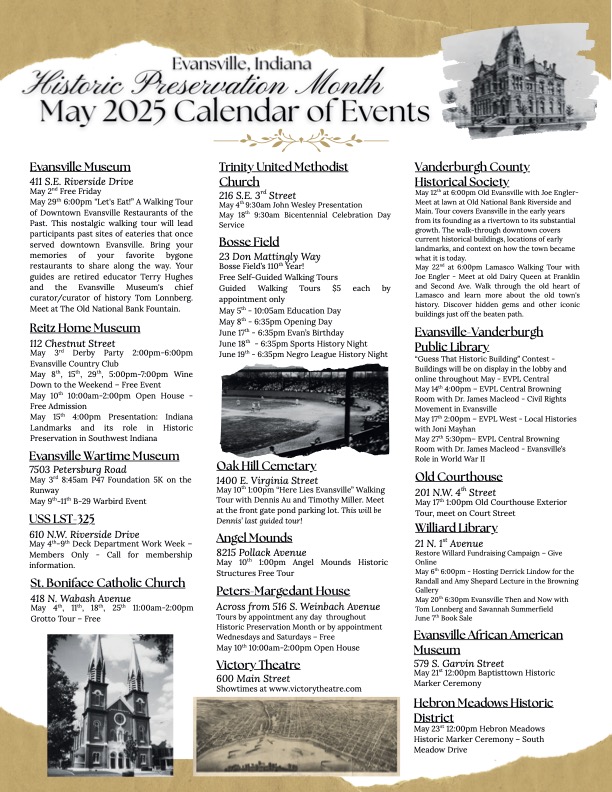

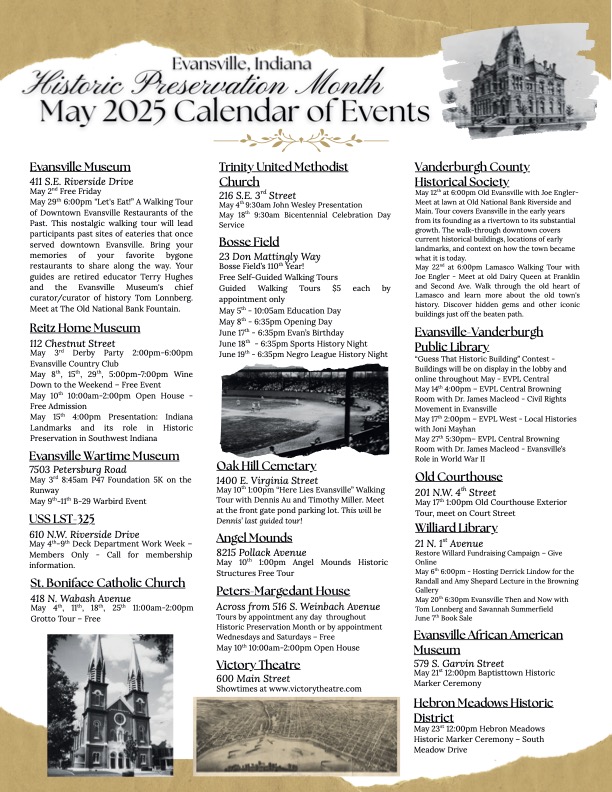

Historic Preservation Month – May 2025!

Promoting and preserving Vanderburgh County's history

Program to Recall Partisan Warfare in Western Kentucky

On Tuesday, May 6 at 6 pm, at Willard Library author and teacher Derrick Lindow will present a talk based on his book We Shall Conquer or Die: Partisan Warfare in 1862 Western Kentucky. He will discuss this deadly and expensive war within a war which was waged behind the lines, often out of the major headlines, and that impacted Evansville as events neared the city. The fighting took hundreds of lives, destroyed or captured millions of dollars of equipment, and siphoned away thousands of men from the Union war effort.

Derrick Lindow is a United States history teacher in Owensboro, Kentucky. He is the 2015 Dr. Tom and Betty Lawrence National History Teacher Award recipient from the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, and the 2019 James Madison Fellow for the state of Kentucky. He is the creator and co-administrator of the Western Theater in the Civil War website, which brings together authors and historians to write about that crucial area of the war.

Evansville Museum’s 2025 Historian in Residence to Present Public Talk

Thursday, March 20, 6 pm

In his talk Antilynching Art and Community Remembrance in Indiana, Dr. Alex Lichtenstein will discuss the compelling history of the use of art and photography to protest against racial violence. His lecture will connect the history of antilynching campaigns to current efforts around the state to commemorate Indiana’s lynch victims.

Alex Lichtenstein is a professor of history at Indiana University, Bloomington, where he chairs the Department of American Studies. His work centers on the intersection of labor history and the struggle for racial justice in societies shaped by white supremacy, particularly the U.S. South (1865-1954) and 20th-century South Africa.

In 1940, Winston Churchill had hoped to get the United States behind its war effort against Nazi Germany, but Franklin Roosevelt and his administration were unable to assist because of a series of neutrality acts passed by Congress. Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe were bombing cities across the UK and by the spring and summer of that year much of western Europe was occupied by German forces.

Roosevelt was coming to the end of his second term and custom, not law, dictated that US presidents would serve only two terms. Though there was strong isolationist sentiment in the US, the invasion and occupation of France turned public opinion and more Americans wanted to assist the British. The Republican Party had a problem because so many of its key leaders were isolationists. The top contenders for the ballot were Robert Taft from Ohio or Arthur Vandenburg from Michigan, both outspoken isolationists. In a surprise move, Wendell Wilkie, a former Democrat, and unseasoned politician was nominated at the GOP’s convention.[1]

Wilkie was born in Elwood, Indiana in 1892. He completed his degree at Indiana University where he had shown some interest in socialism. He later attended the Indiana School of law where he gave a controversial speech that almost prevented him completing his degree. After college, Wilkie had left Indiana and became more associated with business interests in New York. Wilkie was a strange nominee for the GOP given his previous flirtations with radical politics. He had been a New Deal supporter, but changed his mind when the administration created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Wilkie worked as a corporate attorney and became a utilities executive for the Commonwealth and Southern Corporation which had interests in the south where the TVA proposed to create public utilities. While he attacked the TVA, he remained a supporter of New Deal social legislation and he did not wholly adopt the GOP principles of unregulated business.[2]

Wilkie registered as a Republican in 1939 and had never once held a government post. His running mate was Oregon Senator Charles McNary, who supported the public utilities projects that Wilkie opposed. They were an odd pairing for the Party who was trying to run a campaign against a popular president at a time when the US’s traditional allies in Europe were under attack. There were several critics of Wilkie within the Party, but he at least did not have isolationist baggage. His campaign platform was based on his belief that the New Deal was anti-business, but more important, Wilkie had publicly criticized the Nazi regime and its aggressive attacks throughout Europe. He wanted to end the arms embargo in the neutrality acts and send support to Britain. His internationalism was increasingly in line with American sentiment and the growing fears about the fall of the UK, and did not substantially differentiate him from Roosevelt.[3]

Roosevelt was chosen on the first ballot at the Democratic National Convention in July. To placate critics of a third term, Roosevelt appointed Republicans to important foreign policy positions – Frank Knox was appointed secretary of the Navy and Henry Stimson became secretary of war. Stimson was the most significant appointee; he had served under Taft and Hoover and he rejected his Party’s isolationism and advocated aid to Britain.

Wilkie had a great deal going against him in the campaign. He was a poor speaker, he had a checkered past, his movements were so erratic during his speaking that he would move away from microphones. He also had to navigate a Party that was trying to appear interested in helping British allies while placating the isolationist voices that were becoming louder in the GOP. He began his campaign in his hometown in August, and though he did more campaigning than Roosevelt, he was never as popular.[4]

On October 17, 1940, Wilkie brought his campaign to Evansville, the first presidential candidate to visit since John Davis in 1924. His talk was part of a train tour and was only meant to be thirty minutes long. When he arrived, he was transported the 40 blocks from the Union railroad station to Bosse Field. He arrived in the morning and the crowds lined the entire 40 blocks. The journalists traveling with him claimed it was the largest morning crowd in comparably sized cities they had seen on the tour. Inside Bosse Field, 12,000 spectators watched Wilkie while some defied police orders and went up to the podium or stood on tables meant for the press. It became the largest political rally Evansville had ever seen to date and some in the crowd claimed it was the most people they had seen in Bosse Field.[5]

The Evansville Courier described him as “youthful looking,” with “tousled hair,” he waved “good-naturedly” and flashed a big grin “which radiated personality and pleasure.” He allegedly walked to the podium without his hat and some women were overhead remarking that he was handsome and so young to be running for President. Maude Tracewell from Kirkwood Indiana, a former neighbor of Wilkie’s, traveled to Evansville to see his talk. Much to the crowd’s surprise, he kissed her on the lips. He opened his speech talking about how happy he was to be back in Indiana, which he had a “deep affection” for. He told the crowd that he was born and married in Indiana, Phillip, his only child was born in Indiana, and both his parents were buried in Indiana. He claimed his “breath came a little bit quicker and his heart beat a little bit faster upon his return” there.[6]

Completely on brand for Wilkie, he spoke off script “ignoring completely” what he was meant to speak on. He launched into an attack on the New Deal, he claimed that his goal was a job for every household, a phrase that had become a slogan of his campaign and one he claimed his opponents mocked. He believed that the New Deal had done enough and could go no further and that the Democratic Party was not interested in creating jobs or solving the unemployment problem. He promised to work for jobs, and he preached that “there is a future for every boy in America” and a living wage for the “head of every household.”[7]

Wilkie claimed that the New Deal was holding US companies back and that he would “release” US power to allow Americans to be productive. He believed that the fall of France was because the country had become stagnant and weak and had embraced defeatism. He also made a nod toward US diversity claiming that like yeast, the US would begin to produce, and the country would then expand again. He closed his speech with his fist held up in the air and proclaimed: “I have much confidence in industrial leaders, agricultural leaders, and labor leaders and I want to draw them all together, not in conflict but in confidence and cooperation to make this blessed America strong, happy, and free!”[8]

By the time Wilkie had arrived in Evansville, he had abandoned his previous support of Britain under pressure from isolationsists in the Party. But more than domestic issues, Americans were increasingly concerned about having leadership capable of leading the country during war time. Polls showed that many did not believe Wilkie’s promises to keep the US out of war. Roosevelt had also been campaigning on increased production, and the economy had been in gradual recovery which helped the Democrats. The month of his Evansville talk, 6,000 British people were killed in bombing raids, in November that number was 10,000.[9]

Wilkie proved to be too inexperienced for voters. He won only eight states, including Indiana. Most were in the Midwest except for Maine and Vermont which were both states with strong GOP majorities. After the election, he became a vocal Roosevelt supporter and urged US support for the British. He supported the Lend-Lease Act and by the summer of 1941 pushed for direct aid to England. In 1941 he traveled to the UK and the Middle East as a Roosevelt representative. In 1943 he wrote a book titled One World which advocated international cooperation to uphold peace. Though a Roosevelt advocate, he sought the GOP ticket again in 1944, but by then the Party had continued its political move to the right and it nominated Thomas Dewey. In October 1944, at only 52 years old, Wilkie died after a heart attack. Eleanor Roosevelt eulogized him in her regular column “My Day” praising his work against racism and his “honest convictions.”[10]

[1] Peter Feuerherd, “An untested businessman almost became president during World War II,” Jstor Daily, February 27, 2019, https://daily.jstor.org/an-untested-businessman-almost-became-president-during-wwii/.

[2] Gregory, Ross. “Politics in an Age of Crisis: America, and Indiana, in the Election of 1940.” Indiana Magazine of History 86, no. 3 (1990): 257.

[3] Ross. “Politics in an Age of Crisis,” 259, 262.

[4] Ross. “Politics in an Age of Crisis,” 268.

[5] “Wilkie Assails New Deal Here for Defeatism,” Evansville Courier, October 18, 1940, 1-2; “Thousands Greet Wilkie,” Evansville Press, October 17, 1940, 1.

[6] “Wilkie Assails New Deal Here for Defeatism,” 1-2; “Thousands Greet Wilkie,” 1.

[7] “Wilkie Assails New Deal Here for Defeatism,” 1-2; “Thousands Greet Wilkie,” 1.

[8] “Wilkie Assails New Deal Here for Defeatism,” 1-2; “Thousands Greet Wilkie,” 1.

[9] “Wilkie Assails New Deal Here for Defeatism,” 1-2; “Thousands Greet Wilkie,” 1.

[10] Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day, October 12, 1944,” The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition (2017), accessed 11/21/2023, https://www2.gwu.edu/~erpapers/myday/displaydoc.cfm?_y=1944&_f=md056922.

All are invited to a program to mark the centenary of the devastating 1925 tornado with author and expert Justin Harter. Joint program with the Evansville Museum.

Program at Evansville Museum, Sun March 16 at 2pm

Although many people have heard of bodysnatching, most don’t know that it is closely connected to modern medicine. Nor do they know that Indiana had some startling cases of grave robbery by these “resurrectionists” in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In this presentation, Tamara Hunt traces the medical history of bodysnatching and focuses on occurrences in Indiana that made national or even international news.

Dr Tamara Hunt has been a professor at the University of Southern Indiana for twenty years, teaching a variety of courses on European and World History. Among her most popular courses are “Social History of Murder” and “Social History of Ghosts.” The research for those classes led to this study of grave-robbing. She is currently working on a book on publishing in eighteenth century England and is writing a book with her husband, Scott Myerly, on how the ideology of capitalism and chivalry combined to create modern male dress from the medieval period to the early twentieth century.

We regret to announce that due to circumstances beyond our control the “Food Traditions” program scheduled for Thursday 19th September has had to be canceled. We will keep you informed about any make up date as soon as we know about it.